Title

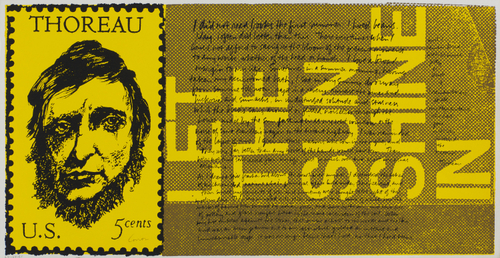

the stamp of thoreau

Year

1969

Archive ID

69-61

Medium

Serigraph

Size

11 ½"h x 22 ½"w

Transcribed Text

I did not read books the first summer; I hoed beans. Nay, I often did better than this. There were times when I could not afford to sacrifice the bloom of the present moment to any work, whether of the head or hands. I love a broad margin to my life. Sometimes in a summer morning, having taken my accustomed bath, I sat in my sunny doorway from sunrise till noon, rapt in a revery amidst the pines and hickories and sumachs, in undisturbed solitude and stillness while the birds sang around or flitted noiseless through the house until by the sun falling in at my west window or the noise of some traveller's wagon on the distant highway. I was reminded of the lapse of time. I grew in those seasons like corn in the night, and they were far better than any work of the hand would have been. They were not time subtracted from my life, but so much over and above my usual allowance.

As I drew a still fresher soil about the rows and my home, I disturbed the ashes of unchronicled nations who in primeval years lived under these heavens, and their small implements of war and hunting were brought to the light of this modern day. They lay mingled with other natural stones, some of which bore the marks of having been burned by Indian fire, and some by the sun, and also bits of pottery and glass brought hither by the recent cultivations of the soil. When my hoe tinkled against the stones, that music echoed to the woods and the sky was an accompaniment to my labor which yielded an instant and immeasurable crop. It was no longer beans that I hoed, nor that I hoed beans and I remembered with as much pity as pride if I remembered at all my acquaintances who had gone to the city to attend the oratorios.

Thoreau

LET THE SUN SHINE IN

As I drew a still fresher soil about the rows and my home, I disturbed the ashes of unchronicled nations who in primeval years lived under these heavens, and their small implements of war and hunting were brought to the light of this modern day. They lay mingled with other natural stones, some of which bore the marks of having been burned by Indian fire, and some by the sun, and also bits of pottery and glass brought hither by the recent cultivations of the soil. When my hoe tinkled against the stones, that music echoed to the woods and the sky was an accompaniment to my labor which yielded an instant and immeasurable crop. It was no longer beans that I hoed, nor that I hoed beans and I remembered with as much pity as pride if I remembered at all my acquaintances who had gone to the city to attend the oratorios.

Thoreau

LET THE SUN SHINE IN

Texto Transcrito

No leí libros el primer verano; Cavé frijoles. No, a menudo lo hice mejor que esto. Hubo momentos en los que no podía permitirme sacrificar la flor del momento presente a ningún trabajo, ya fuera de la cabeza o de las manos. Amo un amplio margen en mi vida. A veces, en una mañana de verano, después de haber tomado mi baño habitual, me sentaba en mi puerta soleada desde el amanecer hasta el mediodía, absorto en un ensueño entre los pinos, los nogales y zumaques, en una soledad y quietud inmutables mientras los pájaros cantaban o revoloteaban silenciosos por el casa hasta que el sol entraba por mi ventana oeste o el ruido de la carreta de algún viajero en la carretera lejana. Me acordé del paso del tiempo. Cultivaba en esas estaciones como maíz en la noche, y eran mucho mejores de lo que hubiera sido cualquier trabajo manual. No fueron tiempo restado de mi vida, sino mucho más allá de mi asignación habitual.

Mientras dibujaba un suelo aún más fresco alrededor de las hileras y mi hogar, removí las cenizas de naciones sin crónicas que en años primitivos vivieron bajo estos cielos, y sus pequeños implementos de guerra y caza fueron traídos a la luz de este día moderno. Yacían mezclados con otras piedras naturales, algunas de las cuales tenían las marcas de haber sido quemadas por el fuego indio y otras por el sol, y también trozos de cerámica y vidrio traídos aquí por los recientes cultivos de la tierra. Cuando mi azada tintineó contra las piedras, esa música resonó en los bosques y el cielo fue un acompañamiento a mi labor que produjo una cosecha instantánea e inconmensurable. Ya no eran frijoles lo que cavaba, ni que cavaba frijoles y recordaba con tanta lástima como orgullo si recordaba a todos mis conocidos que habían ido a la ciudad a asistir a los oratorios.

Thoreau

DEJA QUE PASE EL SOL

Mientras dibujaba un suelo aún más fresco alrededor de las hileras y mi hogar, removí las cenizas de naciones sin crónicas que en años primitivos vivieron bajo estos cielos, y sus pequeños implementos de guerra y caza fueron traídos a la luz de este día moderno. Yacían mezclados con otras piedras naturales, algunas de las cuales tenían las marcas de haber sido quemadas por el fuego indio y otras por el sol, y también trozos de cerámica y vidrio traídos aquí por los recientes cultivos de la tierra. Cuando mi azada tintineó contra las piedras, esa música resonó en los bosques y el cielo fue un acompañamiento a mi labor que produjo una cosecha instantánea e inconmensurable. Ya no eran frijoles lo que cavaba, ni que cavaba frijoles y recordaba con tanta lástima como orgullo si recordaba a todos mis conocidos que habían ido a la ciudad a asistir a los oratorios.

Thoreau

DEJA QUE PASE EL SOL